Not Your Garden Variety Textiles

Fighting Climate Change from the Ground Up with Plant-Based Fibers.

Not Your Garden Variety Textiles

Fighting Climate Change from the Ground Up with Plant-Based Fibers.

Carbon sequestration — the process of capturing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it in the soil, the ocean, or in geologic formations — is one of the best ways to move the climate change needle toward net-zero. As it turns out, certain deep-rooted plants, along with native forests and ocean flora, are ace at sequestering carbon.

Textile innovators and sustainably-minded brands are already developing new technologies to create fibers and fabrics from quick-growing, carbon-sequestering plants, including hemp, abacá, kelp (algae) and mycelium (fungi).

Requiring little or no fertilizer, pesticides, or herbicides, these fibers can be processed by various methods to create knit and woven textiles, faux leathers, and a host of other consumer and industrial products.

Patagonia, prAna, Toad&Co, Levi Strauss and Outerknown have latched on to hemp, known for its strength as well as its ability to capture carbon from the atmosphere at the rate of 1.62 tons of CO2 per ton of hemp. Hemp not only grows quickly, it uses about half the amount of water needed by cotton crops.

But while the Farm Bill passed by Congress in 2018 opened the door to hemp cultivation in the U.S., our hemp textile supply chain is virtually non-existent; most hemp textile products are currently sourced from China.

Hemp Processing Learning Curve

“The U.S. textile market needs to make a commitment to create demand for hemp and invest in the supply chain,” says Dave Petri, founder of Cynosura Consulting. “We need capital investment. Until that happens, hemp textiles will just be a great idea.”

Among those stepping up to the plate is North Carolina’s Bear Fiber, which is focused on developing the American hemp farm-to-fiber-to-finished good value chain in the United States.

Guy Carpenter, president, Bear Fibers, notes that hemp plants grown for fiber are not the same as the plants grown for the CBD industry, which have more lignin, or glue, holding the fibers together in bundles.

“Hemp can be cottonized a couple dozen ways. The most elegant, efficient, practical method has yet to evolve that maximizes sustainability,” Carpenter explains.

Hemp is a bast fiber; unlike cotton it must be decorticated — crushed to remove the hard woody interior from the longer, softer exterior fibers. Degumming removes the lignin, while further processing softens or “cottonizes” hemp into staple fibers so that it can be spun like cotton.

“The short staple fiber has to be consistent in order to spin,” says Carpenter, who adds that there are few spinners in the U.S. who are capable of working with hemp fiber.

In Canada, Bast Fibre Technologies processes hemp and other bast fibers for the non-woven and textile industries. In 2016 the company purchased the IP and other assets of CRAiLAR Technologies.

Processing hemp for textiles in North America will experience a steep learning curve, according to Jason Finnis, chief technical officer for Bast Fibre Tech. “Quality starts in the field,” he explains. Denser planting leads to slender, bamboo-like plants which yield high quality fiber; while gentler, non-aggressive decortication helps preserve it.

The lack of a North American facility for wet processing, or degumming, remains a problem as well. Bast Fibre Tech plans to install degumming in North America within the next two years.

Finnis agrees that spinning is a challenge, as hemp has low elongation, and short fibers and broken ends can result from high-speed spinning. “Big mills live and breathe efficiency — robots can’t handle a significant increase in ends down,” he remarks.

While Asian spinners can spin finer counts, in the U.S. hemp is best spun at 26/1 to 18/1 Ne and lower, and blended with other fibers for denim, outerwear, knitwear, socks and towels.

“The opportunity for hemp is 100 percent there, but it requires outside-the-box thinking,” Finnis believes. “We need to move forward with a systematic approach so that we don’t mess up the opportunity with inferior products.”

Sustainable Alternatives Emerging: Bananas, Pineapple & Algae

Bananatex is a tough, water-resistant woven fabric for bags and packs, made from abacá, a non-fruiting plant from the banana tree family. It’s the brainchild of the team at QWSTION, a Swiss brand of outerwear and accessories with a focus on sustainable solutions.

In 2015 the team discovered abacá growing in the Philippines, where it contributes to reforestation in areas once eroded by palm plantations. The exceptionally strong fibers are stripped from the stalks of the plant and made into a very thin, tear-resistant paper, which is cut into strips and twisted into yarn by a spinner in Taiwan. The resulting fabric is treated with natural beeswax for water resistance, and sewn into bags in China.

“It seems like a lot of companies are currently looking for sustainable alternatives to plastic textiles — the response has been great,” says QWSTION founder and creative director, Christian Kaegi. “We have received interest from countless brands across several industries, from automotive to interior to accessories and footwear, as well as fashion. We have already supplied a few other brands with Bananatex for their products, and have delivered sample yardage to many more. There soon will be several Bananatex products in the market beyond our own.”

Another end-use for alternative plant fibers is animal-free leathers. Piñatex is a non-woven textile, made from Philippine pineapple leaf fiber. Dr. Carmen Hijosa and her company Ananas Anam Ltd, created the first decorticating machine in the Philippines.

The fibers are decorticated, degummed and treated to form a non-woven mesh, which is sent to Spain for specialized finishing, resulting in a sustainable leather alternative. The remaining biomass is used for fertilizer or fuel.

Piñatex is distributed by Ananas Anam and is in demand for footwear, clothing, accessories, home furnishings, and automotive upholstery.

Mylo is a sustainable vegetable leather from Bolt Threads made from mycelium, the branching underground structure of mushrooms that forms vast, carbon-sequestering networks under the forest floor.

Researchers studying carbon sequestration in forest soil believe that fungi such as mycelium are responsible for anywhere from 47 percent to 70 percent of soil carbon found in their samples.

Bolt Threads grows the mycelium on beds of agricultural waste, where it quickly assembles into a mat of interconnected cells. The mat is then harvested, dyed, and compressed to create Mylo, which to date has been made into handsome bags for Stella McCartney and Chester Wallace.

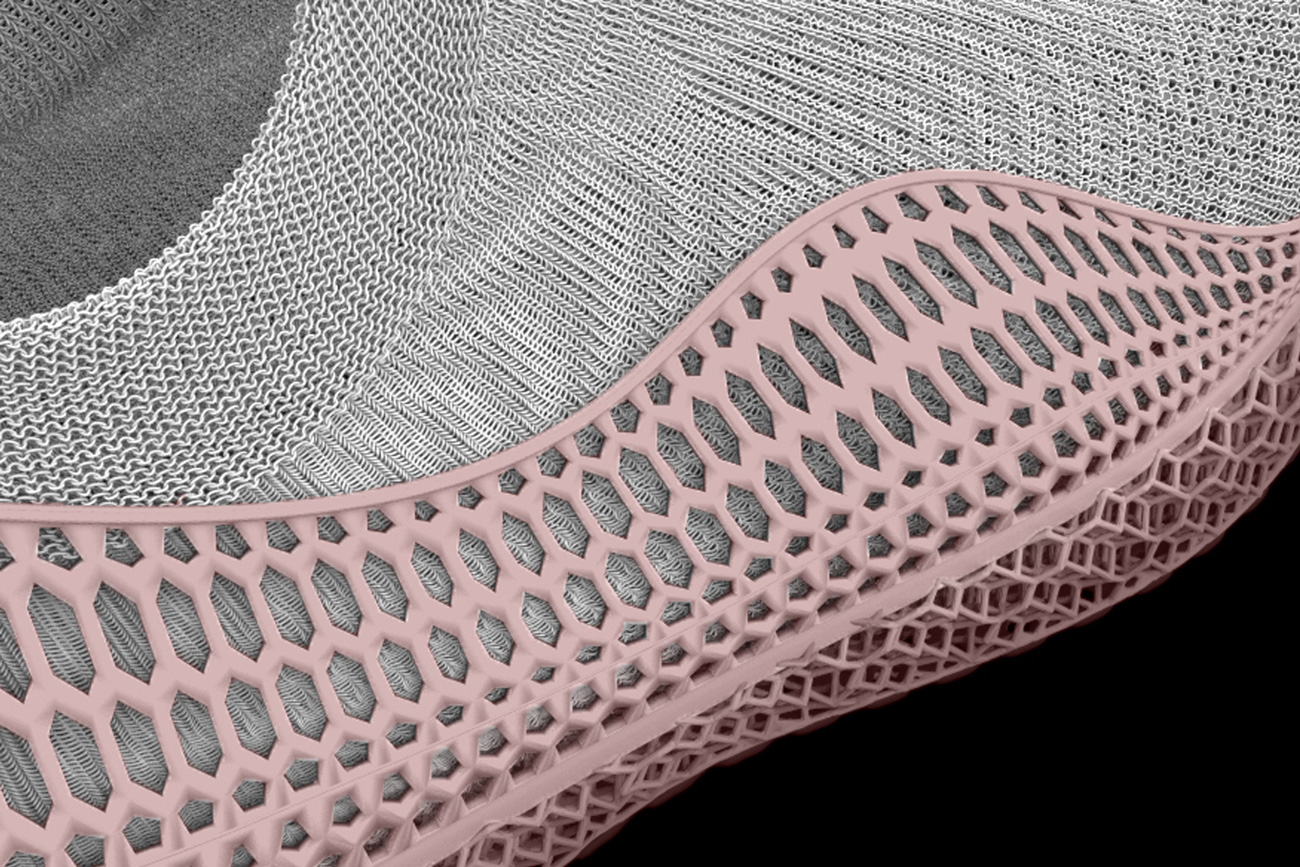

Plant fibers for textiles and apparel are also being harvested from under the sea. AlgiKnit, Inc., a biomaterials company, creates bio-based yarns for apparel and footwear from kelp. The biodegradable yarn is said to be ideal for knitting, illustrated in the company’s prototype AlgiKicks sneaker.

The Carbon Institute, a collection of initiatives in education, research, science and innovation supported by the Greenhouse Gas Management Institute, estimates that macroalgae such as kelp and other seaweeds sequesters about 634m tonnes (metric tons) of CO2 per year, greater than the emissions of Australia.

Countering climate change by managing our carbon emissions to net-zero is a huge task; but cultivating alternative natural fibers that sequester carbon from the atmosphere is a start. “If we are serious about sustainable solutions, we need to look at other natural fibers,” insists Cynosura’s Petri. The textile industry has the potential to fight climate change from the ground up.

%20(1).jpg)

.svg)